In the modern era, it feels impossible to separate baseball from math. Statistics and mathematical applications are everywhere in the sport. From lineup construction and bullpen usage to pitch design and defensive alignments, nearly every corner of the game has embraced analytics in the pursuit of competitive edges.

You do not need to watch Moneyball to understand that this acceptance took decades to arrive. There was a time when advanced statistics were neither accessible nor widely accepted. Today, if I wanted to, I could build a predictive pitching model on my laptop using my own definition of “stuff,” and so could a million other people. That kind of access simply did not exist for earlier generations.

To put it in perspective, Davey Johnson, the subject of this article, had to rely on a computer housed at a local Baltimore brewery just to test some of his statistical ideas. It was cumbersome, limited, and far from user friendly. Yet even then, there were people around the game who seemed to instinctively understand truths that would not be formally proven until decades later.

Ted Williams is perhaps the most famous example. His understanding of hitting still aligns with modern instruction today. Williams and Branch Rickey were both strong advocates of on-base percentage long before it became mainstream. Rickey once remarked that a walk was worth roughly 75 percent of a hit. That estimate is remarkably close to how walks and singles are weighted today in metrics like wOBA, which typically place walks in the high 70 percent range of a single’s value.

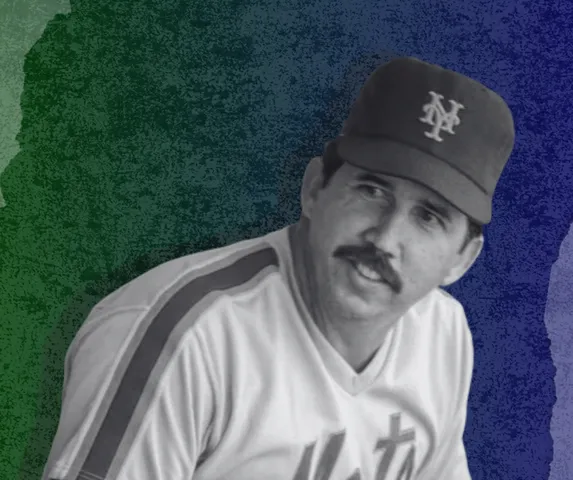

Another figure who belongs in this group of early analytical thinkers is Davey Johnson.

Learning Under Earl Weaver

Davey Johnson spent most of his Major League playing career with the Baltimore Orioles under Earl Weaver, a manager whose philosophy would later be recognized as deeply analytical. Weaver and Johnson shared many traits. Both were slow-footed second basemen who generated offensive value by getting on base rather than by power or speed. Both were stubborn. Both were confident in their ideas.

They also clashed frequently.

Johnson was constantly suggesting ideas to teammates and even to Weaver himself. In one famous example, Johnson suggested that Orioles pitchers should aim down the middle of the plate more often when they found themselves in unfavorable count situations. His reasoning was based on probability and outcome distribution, though he did not have the data to formally prove it.

Teammates like Jim Palmer mocked him for the idea, calling him “Dum Dum.” Decades later, analysts such as Tom Tango and Kyle Boddy would arrive at similar conclusions using pitch tracking data and heat maps. Johnson had reached the same conclusion more than half a century earlier using intuition and reasoning alone.

Johnson also created statistically driven lineup suggestions for Weaver. Weaver never used them, but the fact that Johnson was building them at all showed an early managerial mindset rooted in evidence and probability.

A Mathematical Mind Meets the Game

Johnson’s intuition was backed by formal training. He was a math major in college and had taught himself computer science concepts as well. During the 1970s, while still playing for the Orioles, he began developing mathematical theories about baseball decision making.

Using the brewery computer, Johnson ran simulations to test his ideas. These were crude by modern standards, but they represented something radical at the time. He was attempting to model baseball outcomes mathematically, not just philosophically.

Eventually, he would get the chance to apply those theories on the field.

From the Minors to the Major Leagues

Between 1979 and 1984, Johnson managed several minor league teams. It was during this period, particularly with the Mets Triple-A affiliate, that his ideas truly took hold. The results spoke for themselves.

In 1984, Johnson was hired to manage the New York Mets at the Major League level. With the Mets, he fully implemented a style that blended Earl Weaver’s run expectancy ideas with his own analytical thinking.

The numbers are telling. During his tenure, the Mets laid down sacrifice bunts 23 percent less often than the league average. They issued intentional walks 39 percent less frequently. They attempted steals of third base 31 percent less often. These decisions were grounded in run expectancy logic well before that language entered the mainstream.

Johnson led the Mets to a World Series championship in 1986.

A Career That Spanned Eras

Unlike many of his contemporaries, Johnson’s openness to analytics allowed him to remain relevant well into later eras of the game. He managed into the 2010s, which means he managed players as different as Keith Hernandez and Bryce Harper.

Johnson finished with a .562 career winning percentage, second all-time among managers with color photographs, behind only Earl Weaver, with a minimum of 1,000 wins. He won Manager of the Year twice and has a resume that should already place him in the Hall of Fame.

Even if one were to ignore his on-field success, which would be difficult to justify, Johnson’s contributions to the evolution of baseball strategy alone make a compelling Hall of Fame case.

Instincts That Never Left Him

Johnson’s instincts followed him to the very end of his baseball life.

In 2009, he was managing the DeLand Suns of the Florida Collegiate League. A shortstop from Stetson University, coming off an unremarkable sophomore season, joined the team for the summer. At the request of Stetson’s head coach, Johnson occasionally allowed the player to pitch.

Once Johnson saw him throw, he never allowed the player to return to the field. He used him exclusively as a reliever. Despite posting six scoreless innings, the player grew frustrated and quit the team.

When he returned to Stetson, the coaching staff informed him, at Johnson’s suggestion, that he would convert to pitching full time. Three years later, Johnson would manage the Washington Nationals. Three years after that, the same former shortstop was pitching in Single-A for the Mets.

His name was Jacob deGrom.

A Manager for Any Era

Davey Johnson was ahead of his time, but he was also exceptional within his own time. He was a World Series champion as both a player and a manager, a pioneer of analytical thinking, and a leader whose ideas helped shape modern baseball strategy.

Few managers could thrive across multiple eras of the game. Johnson did. He understood winning in a way that transcended trends, technology, and tradition.

That understanding is why his absence from the Hall of Fame remains one of baseball’s most glaring oversights.

If this was your kind of read, you’ll like what’s next. Get The Sandman Ticket, our free, weekly newsletter with picks, insights, and a little bit of everything we love about sports.